A United Federal Britain

This post follows on from Optimising Federalism.

(And Northern Ireland. I considered the title “Federal United Kingdom”, then binned that for obvious reasons. Seriously, after the whole North Macedonia thing, it should be clear that deciding what a country is called is just an absolute minefield.)

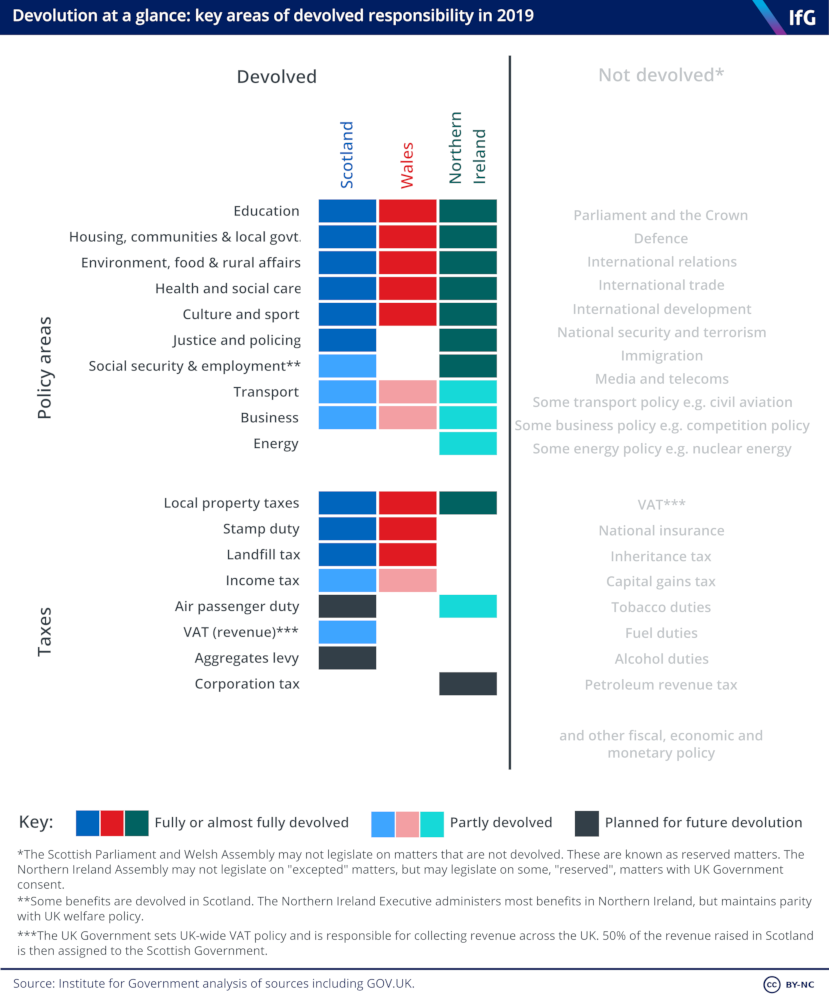

Currently, there are various levels of devolved power in the UK. There are the four main countries – England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Devolution is applied inconsistently across these, with Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland heavily devolved with their own legislatures (the Scottish Parliament, Northern Ireland Assembly and Senedd Cymru respectively). England does not have its own devolved parliament, and instead is governed directly by the national parliament at Westminster. This has given rise to what is known as the West Lothian question, which queries the legitimacy of a system in which a Scottish MP gets a vote in something that affects England but not Scotland, whilst an English MP does not have a reciprocal power as such matters are decided by the Scottish Parliament.

This is not the only glaring inconsistency however – each of the countries with a devolved parliament receives different devolved powers from the national government. Scotland and Northern Ireland also have separate legal systems from England, but Wales shares the same legal institutions and has only been able to set laws independently from Westminster since 2006.

Then there is London, which has a devolved executive – the Mayor and the London Assembly. This gives London a large degree of autonomy from the central government when it comes to things like infrastructure spending and strategic planning, but it misses out on many of the powers that the devolved countries are granted, and has no devolved legislature at all.

Other large cities have seen increasing devolution in recent years, for instance Greater Manchester has had a directly elected mayor since 2017. There are now several cities that have benefitted from such devolution, but again both the structure of the authority and the devolved powers they have are often inconsistent.

The UK has long been a very centralised state, which can leave certain areas to be forgotten about by the national government, being left to wither – an issue that has been written about at length, and has been noted yet again in this Economist article. Of course, all of the areas mentioned above have benefitted from varying degrees of decentralisation as a result of devolution, but:

- There are many areas that have experienced no devolution, and so are in effect still governed with disinterest from afar.

- The areas that have seen some devolution are treated inconsistently, leading to unnecessary complexity.

- The devolution of power is (at least in principle) still entirely at the discretion of the central government in Westminster, and can be rescinded at any time.

As might be clear from the last few posts, I think federalism is a good way to improve the state of democracy in a large unitary country. The fact that the UK is already part-way along this road, having significant devolution to various areas, should make a transition towards federalism a welcome simplification. I will follow the guidelines from the previous post to design regions that should facilitate a federation that runs smoothly. These are:

- No state should be larger than 8 times the population of the smallest.

- All states should be between 200k and 25.6m in population, or more ideally between 800k and 6.4m.

- Where a region contains rural areas and a large contiguous city, if both are large enough in population to be separate states, they should be.

Given this preamble, if you want to skip to where I start getting to the point, click here. If all you want is the final proposal, click here instead. Otherwise, let us begin.

Where to Start

So, first things first – what if we just took the four main countries plus London (with its devolved executive) and gave them all the same powers as equal states in a federation?

| State | Population |

|---|---|

| England (exc. London) | 44,800,000 |

| London | 8,170,000 |

| Scotland | 5,310,000 |

| Wales | 3,060,000 |

| Northern Ireland | 1,810,000 |

Even having removed Greater London from England, it is still far too large and would be completely dominant in any federation. England is well over the 25.6 million limit discussed in the previous post, and it is almost 25 times the size of Northern Ireland.

Northern Ireland itself is fairly geographically isolated and culturally distinct, so combining it with any other areas to reduce the difference between the largest and smallest states is a complete non-starter. This gives us a hard limit on the size of the largest state that we can accept. If Northern Ireland is the smallest state, and we want no state to be more than 8 times the population of the smallest state, we are limited to a maximum state size of 14.5 million people.

Combined Authorities

Outside of London, there are several more “combined authorities” with devolved funding, powers and directly elected mayors. These are often city regions, so separating these from their rural surroundings could be an easy win. Using these to split England further gives us the following 15 entities and populations:

| State | Population |

|---|---|

| England (exc. Various) | 28,900,000 |

| London | 8,170,000 |

| Scotland | 5,310,000 |

| Wales | 3,060,000 |

| West Midlands (Birmingham) | 2,830,000 |

| Greater Manchester | 2,760,000 |

| West Yorkshire (Leeds) | 2,320,000 |

| Northern Ireland | 1,810,000 |

| Liverpool City Region | 1,530,000 |

| Sheffield City Region | 1,390,000 |

| North East (Sunderland & Durham) | 1,160,000 |

| West of England (Bristol & Bath) | 1,120,000 |

| Cambridge and Peterborough | 847,000 |

| North of Tyne (Newcastle & Northumberland) | 826,000 |

| Tees Valley | 702,000 |

Despite removing these 10 combined authorities, some of which are large cities, what is left of England is still almost as big as all of the other states combined, which is unacceptable. We have also now introduced several even smaller entities – the state of England is now 41 times larger than Tees Valley.

Regions

For statistical purposes, the UK is divided into 12 “Regions” that currently have no distinct governmental powers. Many proposals of federalism in the UK have used these, so we can see what we would get if each of these were turned into a state:

| State | Population |

|---|---|

| South East | 8,630,000 |

| London | 8,170,000 |

| North West | 7,050,000 |

| East of England | 5,850,000 |

| West Midlands | 5,600,000 |

| Scotland | 5,310,000 |

| South West | 5,290,000 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 5,280,000 |

| East Midlands | 4,530,000 |

| Wales | 3,060,000 |

| North East | 2,600,000 |

| Northern Ireland | 1,810,000 |

These are relatively evenly sized – the South East has around 5 times the population of Northern Ireland, which is acceptable. These divisions have been around for a while though, and they have not taken off as actual administrative regions for a reason. Most of them contain a mixture of cities and rural areas that do not naturally work together.

Regions & Combined Authorities

If we now split the combined authorities from the regions, we generate 21 states:

| State | Population |

|---|---|

| South East | 8,630,000 |

| London | 8,170,000 |

| Scotland | 5,310,000 |

| East of England | 5,000,000 |

| East Midlands | 4,530,000 |

| South West | 4,170,000 |

| Wales | 3,060,000 |

| West Midlands (Birmingham) | 2,830,000 |

| North West | 2,770,000 |

| West Midlands (Excluding Birmingham) | 2,770,000 |

| Greater Manchester | 2,760,000 |

| West Yorkshire (Leeds) | 2,320,000 |

| Northern Ireland | 1,810,000 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 1,570,000 |

| Liverpool City Region | 1,530,000 |

| Sheffield City Region | 1,390,000 |

| North East (Sunderland & Durham) | 1,160,000 |

| West of England (Bristol & Bath) | 1,120,000 |

| Cambridge and Peterborough | 847,000 |

| North of Tyne (Newcastle & Northumberland) | 826,000 |

| Tees Valley | 702,000 |

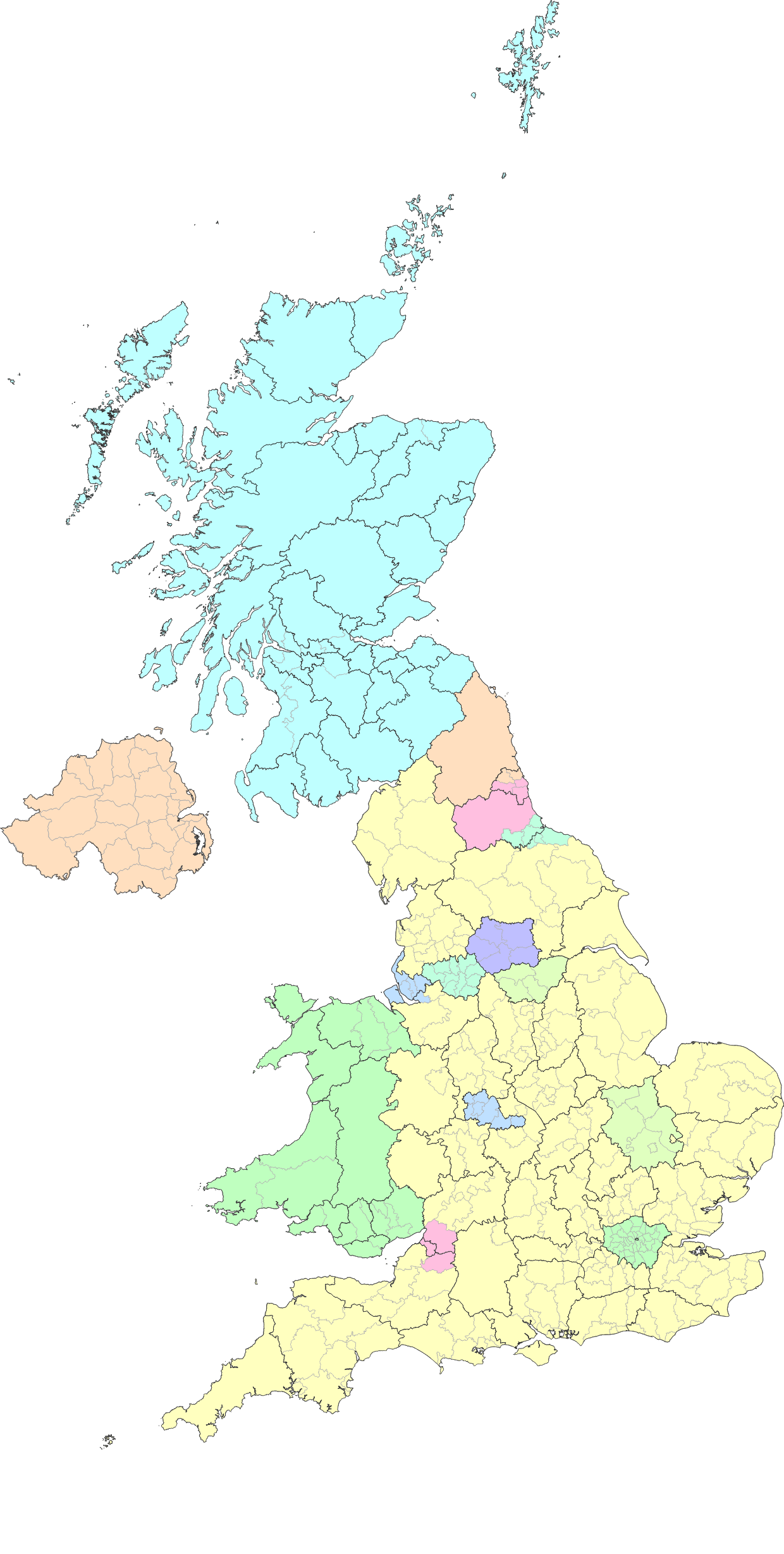

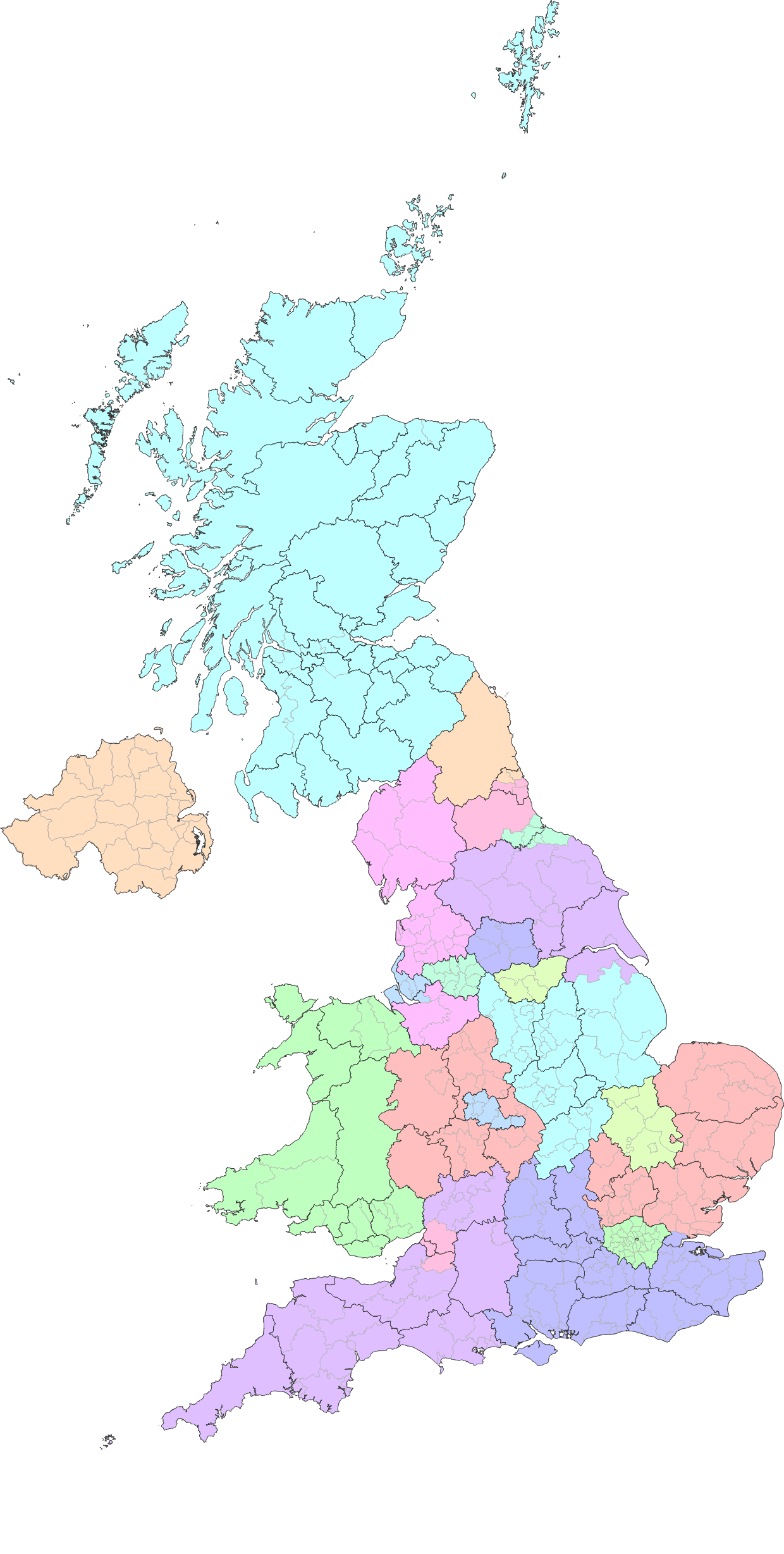

Splitting out the large cities in this manner makes the divisions far more likely to be functional – their respective governments will be able to focus their attentions on the relevant rural or urban issues respectively. Unfortunately however, the South East now has over 12 times the population of Tees Valley. As can be seen from the map, there is also an aesthetic issue – some of the regions have holes in them. This is not necessarily an issue, but it does make them look quite untidy which could make them unpopular, and be a barrier to implementation.

This is a good start though – from this basis, we can design states for the UK. We want them to be comfortably within the size limits, moderately consistent in character (urban or rural) and reasonably natural feeling, respecting local identities.

Going Further

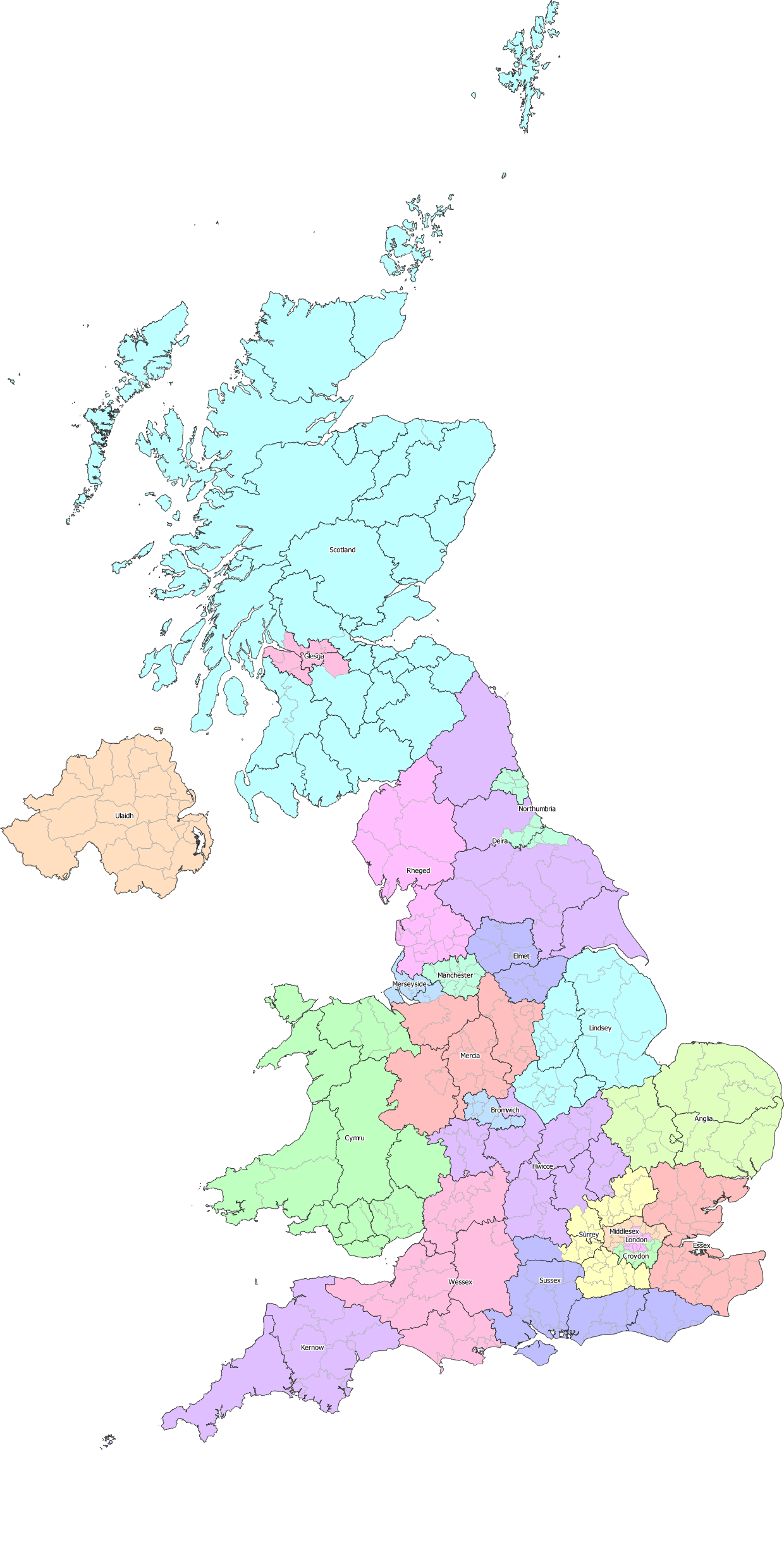

We can make adjustments to these 21 states to improve the proposal dramatically. For ease of reference, I will also suggest appropriate names for the proposed states that are a little less unwieldy. Most will be based on ancient kingdoms that occupied similar areas during the Heptarchy:

Kernow (Cornish for Cornwall)

Cornwall has a fairly independent streak, and although on its own it has quite a small population, Cornwall and Devon together are culturally similar and have a combined population of 1,750,000 which can be split from the rest of the South West.

Wessex (after the ancient Saxon kingdom)

West of England (Bristol & Bath) has a significantly lower population density than the other city-regions, so it could be combined with the remainder of the South West to form a state with a population of 3,540,000.

Essex (after the ancient Saxon kingdom) and Surrey (after the county of Surrey)

The “Home Counties” bordering London are quite different in character to areas further away from the capital. Essex, Hertfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Berkshire, Surrey and Kent are all part of London’s commuter belt, giving them their own particular concerns and interests different to other parts of the UK.

Due to their population density, all of these counties combined would make for a very populous state, so it would make sense for there to be two such states. The difference between the Western and Eastern home counties is probably greater than the difference from North to South, as Essex and Kent both have coastlines and significant industry, while the other counties further inland have a very service heavy economy and are some of the wealthiest areas of the UK outside London.

This suggests that the counties of Essex and Kent could form one state (Essex) with a population of 3,070,000. The remaining home counties could form another state (Surrey), though excluding the districts of West Berkshire, Aylesbury Vale and Milton Keynes which are still fairly distant from London. This would give the state of Surrey a population of 3,460,000.

Sussex (after the ancient Saxon kingdom)

With the home counties removed, the Southern parts of the South East (Hampshire, the Isle of Wight, East Sussex, West Sussex and West Berkshire) can form the state of Sussex with a population of 3,240,000.

Anglia (after the ancient Angle kingdom)

Cambridge and Peterborough is a little on the small side, but with the home counties removed from the East of England region, its remnants (excluding Bedfordshire, which we will use later) can be combined with Cambridge and Peterborough to form the state of Anglia with a population of 2,720,000.

London, Middlesex and Croydon

London is often split into Inner and Outer London for statutory and statistical purposes. Outer London is further divided by the river Thames, with areas to the north of the Thames being quite different in character from the south due to greater tube network coverage, greater population density and having required much greater reconstruction following the second world war. Inner London (as defined by the ONS for statistical purposes) has a population of 3,230,000 and should probably continue to be referred to as London. North Outer London (North London as defined by the Boundary Commission, excluding areas of Inner London) has a population of 3,150,000 and overlaps significantly with the old county of Middlesex. South Outer London has a population of 1,790,000 and the largest city it contains is Croydon. Splitting London into 3 parts should not stop them coordinating on large projects such as the Oyster network.

Bromwich (from Beorma)

Beorma is the root of Birmingham, West Bromwich and Bromsgrove. Bromwich therefore seems like an appropriate name for the state made from the combined authority of the West Midlands (Birmingham).

Mercia (after the ancient Angle kingdom)

The rest of the West Midlands has a large hole cut out of it for Bromwich, Splitting Shropshire and Staffordshire on the top from Herefordshire, Worcestershire and Warwickshire on the bottom. There are better things we can do with the bottom 3, so it makes sense to remove them from Mercia, but this leaves quite a small state. Cheshire in the North West is separated from the rest of the North West by Liverpool and Manchester, so this can be added to Mercia instead. The M1 forms a natural dividing line close to the border between Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire, so we can move Derbyshire from the East Midlands to Mercia as well, giving a population of 3,530,000.

Cymru (Welsh for Wales)

Herefordshire shares a border with Wales and is much more sparsely populated than any of the English counties that it borders (it is actually one of the least densely populated counties in England). In this respect it likely has more governmental requirements in common with Wales than with other counties in the midlands. In fact, the prevalence of farming in Herefordshire, along with significant Welsh cultural presence in the western parts of the county have led to previous proposals to shift the Welsh border to include Herefordshire. Following through with this would make a lot of sense and only increases the population of Cymru to 3,260,000.

Hwicce (after the ancient Saxon kingdom)

In between the states so far defined, we have a number of counties that we have not done anything with. Worcestershire, Warwickshire, Oxfordshire, Bedfordshire and the districts of Aylesbury Vale and Milton Keynes can be combined into a state in the centre of England. Adding Northamptonshire too, from the East Midlands brings its population to 3,700,000.

This English heartland sits on the border between the North and the South, and is sandwiched between London and Birmingham making it extremely well connected and an attractive hub for many logistics firms. This region also contains the majority of the so called “Brain Belt“, including Oxford, Bicester, Milton Keynes and Bedford, which along with Warwick have an unusually high density of headquarters for international and high-tech firms.

Far from being a contrived amalgamation of disparate areas, this state is fairly internally consistent, and would be the third wealthiest state per capita after London and Surrey. The ancient kingdom of the Hwicce was made up in large parts from the Cotswolds, Worcestershire and Warwickshire, but there is evidence for its influence reaching as far east as Northamptonshire and Rutland, making it an apt namesake.

Lindsey (after the ancient Angle kingdom)

Having lost Derbyshire and Northamptonshire, the East Midlands can reclaim the unitary authorities of North Lincolnshire and North East Lincolnshire from their bizarre inclusion within Yorkshire and the Humber. This gives Lindsey a population of 3,060,000.

Elmet (after the ancient Celtic kingdom)

Sheffield would be a relatively small state. Although Sheffield and Leeds both have their own combined authorities, they are only 35 miles apart, and are effectively joined into a single metropolitan area by the cities of Barnsley and Wakefield. By combining West Yorkshire with the Sheffield City Region, we can create a larger metropolitan region covering much of South West Yorkshire with a population of 3,700,000.

Northumbria (after the ancient Angle kingdom)

North of Tyne only incorporates the northern half of the “Tyne and Wear Metropolitan County” (a fairly large conurbation including Sunderland), but it also includes Northumberland which is very rural. Combining the Tyne and Wear Metropolitan County with Tees Valley gives us a metropolitan region with a population of 1,830,000. This region is split in two by County Durham, but we can deal with this later. The remainder of the North East region plus Northumberland have a population of only 766,000 which could be combined with the remaining Yorkshire and the Humber region.

Deira (after the ancient Angle kingdom)

After losing North Lincolnshire, North East Lincolnshire and Leeds, the Yorkshire and the Humber region can absorb what is left of the North East region from above, giving a state that is very large geographically, but very rural, with a population of 2,350,000. This state would contain only two moderately sized cities (York and Hull), but would contain three large National Parks (North York Moors NP, Yorkshire Dales NP and Northumberland NP) and four Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (Northumberland Coast AONB, North Pennines AONB, Nidderdale AONB and Howardian Hills AONB).

Rheged (after the ancient Celtic kingdom), Merseyside and Manchester

With the North West already excluding Liverpool and Manchester, and having moved Cheshire into Mercia, it is left with a population of 1,710,000. Greater Manchester can be left unchanged and the city-region of Liverpool (Merseyside) can incorporate the fairly urban unitary authority of Warrington.

Glesga (Scots for Glasgow) and Scotland

Glasgow is a very large urban area within the largely rural Scotland. Splitting it into its own state would make governing much more straightforward, and would not stop Scottish and Glaswegian governments from working together on projects if they felt so inclined. Specifically, taking the combined councils of West Dunbartonshire, East Dunbartonshire, North Lanarkshire, Inverclyde, Renfrewshire, East Renfrewshire and Glasgow City as a separate state from the rest of Scotland would result in a metropolitan state of 1,550,000 people and a largely rural state of 3,750,000.

Ulaidh (Gaelic for Ulster)

As before, no changes need to be made to Northern Ireland. A more interesting name wouldn’t hurt though.

Proposal Based on Existing District Borders

This gives us the following 23 states:

| State | Population |

|---|---|

| Scotland | 3,750,000 |

| Elmet | 3,700,000 |

| Hwicce | 3,700,000 |

| Wessex | 3,540,000 |

| Mercia | 3,530,000 |

| Surrey | 3,460,000 |

| Cymru | 3,260,000 |

| Sussex | 3,240,000 |

| London | 3,230,000 |

| Middlesex | 3,150,000 |

| Essex | 3,070,000 |

| Lindsey | 3,060,000 |

| Bromwich | 2,830,000 |

| Manchester | 2,760,000 |

| Anglia | 2,720,000 |

| Deira | 2,350,000 |

| Northumbria | 1,830,000 |

| Ulaidh | 1,810,000 |

| Croydon | 1,790,000 |

| Kernow | 1,750,000 |

| Merseyside | 1,740,000 |

| Rheged | 1,710,000 |

| Glesga | 1,550,000 |

These 23 divisions would probably suffice – the largest (Scotland) is now less than 2.5 times the size of the smallest (Glesga), and they might generate more enthusiasm for becoming federal states due to having greater internal similarities than the current statistical regions.

- The densely populated metropolitan states of London, Middlesex, Croydon, Bromwich, Manchester, Merseyside, Elmet, Northumbria and Glesga have autonomy to manage their affairs free from the demands of more rural constituents

- The commuter belt states of Essex and Surrey can easily collaborate with the three states making up Greater London on issues such as transport links and the greenbelt.

- The semi-rural states of Wessex, Hwicce, Sussex, Anglia, Mercia, Lindsey and Rheged have a lower population density than the commuter belt, but are still dotted with bustling towns and small cities.

- The very rural states of Kernow, Cymru, Ulaidh, Deira and Scotland each have their own particular cultures and requirements, which make them cohesive states despite their remoteness.

Making Use of Existing Features

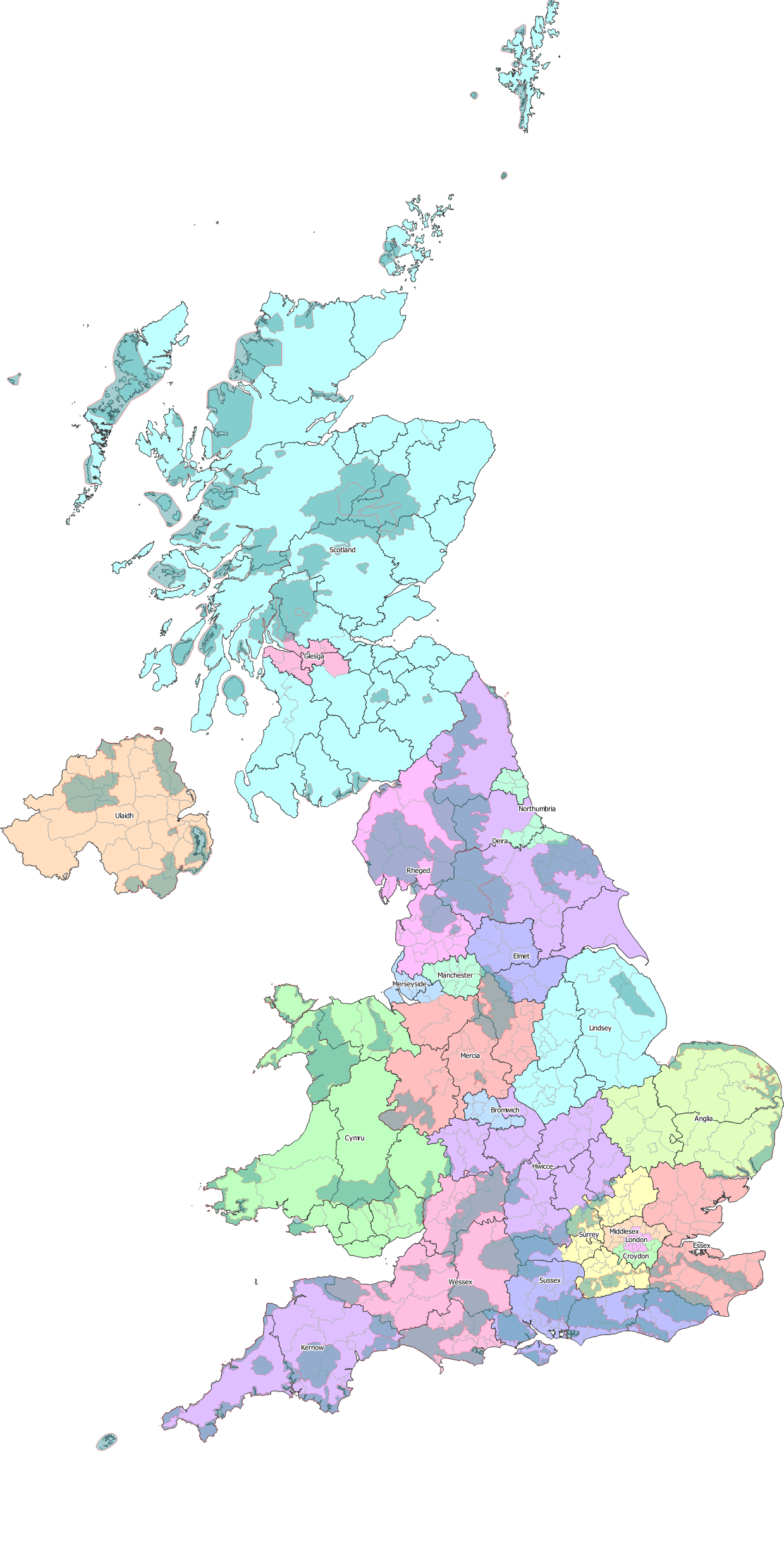

By relying on existing county and district borders, we have exhausted the low hanging fruit, but we can still do slightly better. There are a few more issues that it would be good to address, that will be possible if we allow ourselves to use roads, railways, rivers and National Parks/AONBs as borders as well.

The map below shows the National Parks, AONBs and National Scenic Areas (Scotland) overlaid upon the proposal based on district borders:

We can pick through the proposal above and make finer adjustments to try to resolve issues and make the states as cohesive as possible:

- Northumbria is split into two by the very sparsely populated County Durham in Deira. Rather than moving the whole of County Durham into Northumbria, we can simply include the city of Durham itself, and anything East of it. This joins the two parts of Northumbria together whilst maintaining the high population density of a metropolitan state.

- There are several large, very densely populated cities on the south coast (Bournemouth, Southampton, Portsmouth and Brighton) that are likely to have very different focuses from the surrounding rural counties that make up the rest of our state of Sussex. We can split these off, along with the Isle of Wight into a new metropolitan state. I will name this Solent after the strait of water between the South coast of England and the Isle of Wight. This is actually not a completely new idea, and a “Southern Powerhouse”/”Solent City” has been mooted before (though not without controversy).

- The fringes of Glesga turn very quickly into very rural Scotland (West Dunbartonshire actually includes some of the Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park). Trimming some of this off, allowing the rural areas to be governed by Scotland would be sensible, whilst the densely populated North of South Lanarkshire (Rutherglen, Cambuslang, East Kilbride and Hamilton) are within the metropolitan area of Glasgow, so should be included.

- The Western edges of the Yorkshire Dales National Park and the North Pennines AONB are in Rheged. By shifting the border between Deira and Rheged to the river Eden, this is avoided.

- Kernow is significantly less densely populated than Wessex, but most of Exmoor National Park is in Somerset rather than Devon. National Parks and AONBs tend to have few residents, so it would be appropriate to move the rest of Exmoor NP, the Blackdown Hills AONB and all of the Quantock Hills AONB into Kernow.

- With Herefordshire now being part of Cymru, the small sliver of Gloucestershire that is West of the river Severn is on the wrong side of a very natural border. Moving this area to Cymru removes another very sparsely populated area from Wessex. This area includes the Wye Valley AONB which currently straddles the border with Wales.

- The counties of Essex and Kent are both quite large, extending a long way from London, which makes the Northern reaches of the county of Essex as well as High Weald AONB in Kent quite different in character from their more London focused parts. These areas could be ceded to Anglia and Sussex respectively, to better match their composition.

- The North Wessex Downs AONB covers most of West Berkshire, but extends beyond it in most directions. Now that the densely populated Solent has been removed from Sussex, it is a much more rural state than the others surrounding it, making it sensible for the entirety of this AONB to be included within it. This being said, the name of the AONB might need to be changed, due to it being in the state of Sussex rather than Wessex. “The Berkshire Downs” would probably suffice. Notably, combined with the change above, Sussex now contains all of the North Wessex Downs AONB, the High Weald AONB and the South Downs National Park, which means that an even higher percentage of its land is covered by conservation areas than Deira.

- Bromwich is surrounded by a few towns that might benefit from being served by the same government as the metropolis itself. Bromsgrove, Redditch, Nuneaton and Tamworth could all be considered commuter towns of the Birmingham conurbation. Also, by including Nuneaton we remove the hook that protrudes from the North of Hwicce.

- Greater London is surrounded by the natural border of the M25, while the North and South circulars (the A406 and the A205) serve as a very natural border for inner London.

- Other borders can be tidied up a little, following rivers, railways or roads where they are fairly close to the existing county border.

(As a side note, if we are using roads as borders, it is worth putting the border such that the road itself is clearly inside one or other of the states. If jurisdiction and responsibility over the road is not clear, it may not be maintained, and could be a source of conflict between the states. This is an implementation detail, and therefore not something represented in the maps below, but it is important to consider in any proposal changing border lines.)

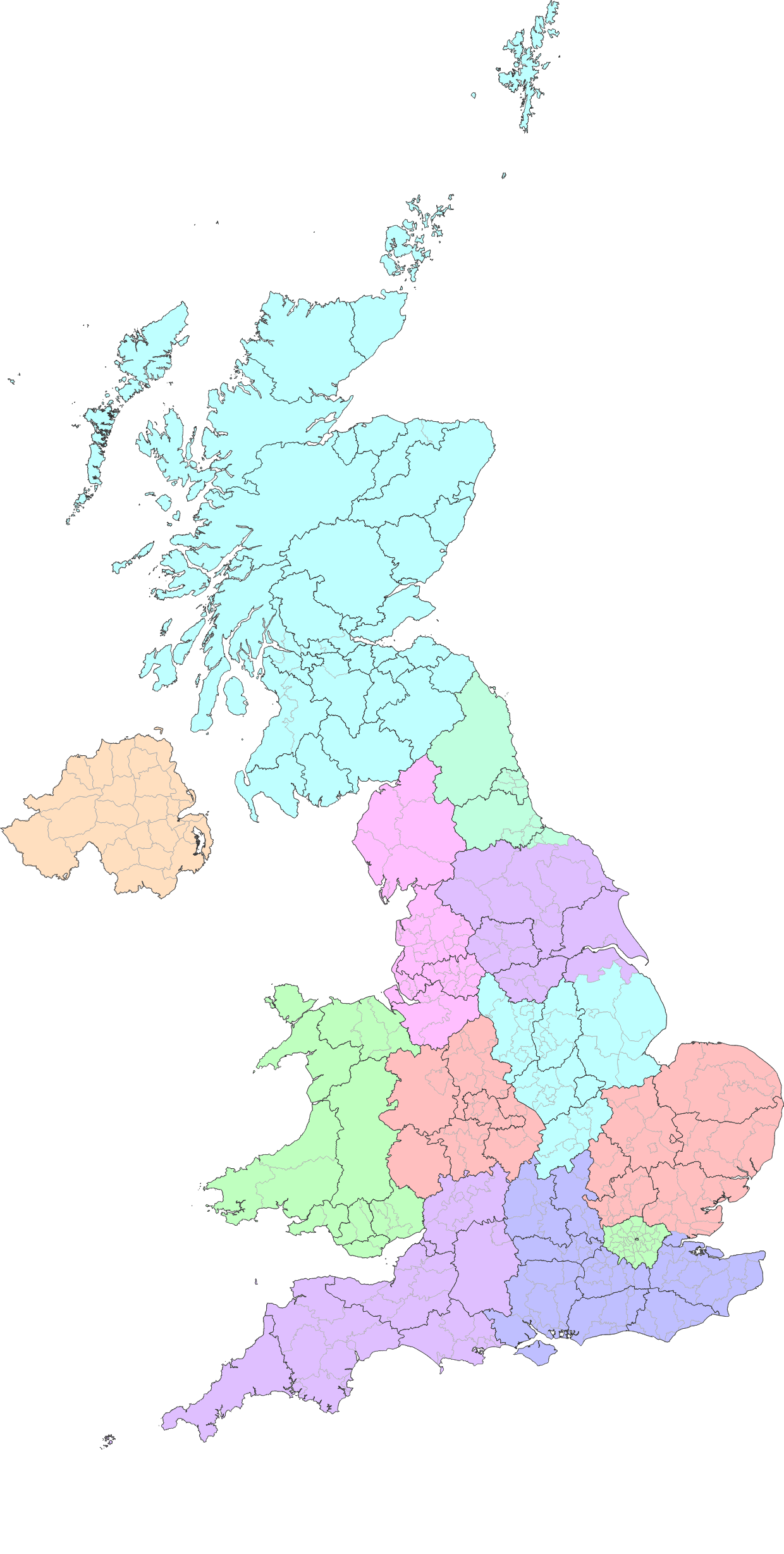

This gives us the following map showing the starting point using existing county and district boundaries, the areas that are to change hands, coloured in various shades depending on which state they are going to be a part of, and the final proposal:

Final Proposal

Importing the data into Google Maps allows me to show a zoomable map of these states (click on a state for more details):

The final 24 states have the populations, areas and population densities as shown below, this time ordered by density:

| State | Population | Area (km²) | Density (per km²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| London | 3,520,000 | 386 | 9,115 |

| Middlesex | 2,900,000 | 995 | 2,911 |

| Croydon | 2,630,000 | 932 | 2,821 |

| Manchester | 2,770,000 | 1,399 | 1,982 |

| Bromwich | 3,270,000 | 1,745 | 1,876 |

| Merseyside | 1,860,000 | 1,228 | 1,519 |

| Glesga | 1,650,000 | 1,163 | 1,421 |

| Elmet | 3,310,000 | 2,497 | 1,324 |

| Northumbria | 2,200,000 | 1,969 | 1,119 |

| Solent | 2,480,000 | 2,263 | 1,096 |

| Surrey | 3,120,000 | 4,360 | 716 |

| Essex | 2,810,000 | 4,906 | 572 |

| Wessex | 2,890,000 | 10,050 | 288 |

| Mercia | 3,230,000 | 11,783 | 274 |

| Lindsey | 3,110,000 | 11,491 | 271 |

| Hwicce | 2,540,000 | 9,893 | 257 |

| Rheged | 1,890,000 | 7,964 | 237 |

| Sussex | 1,640,000 | 8,195 | 200 |

| Anglia | 3,030,000 | 15,410 | 197 |

| Kernow | 1,800,000 | 11,464 | 157 |

| Cymru | 3,340,000 | 23,359 | 143 |

| Ulaidh | 1,810,000 | 14,222 | 127 |

| Deira | 1,970,000 | 20,527 | 96 |

| Scotland | 3,640,000 | 77,478 | 47 |

You can see that the largest state (still Scotland) now has just over twice the population of the smallest (Sussex), so there should be no California/Wyoming problems here. Half of the states (12) are varying degrees of rural, with population densities below 300 people per square kilometer. Around half the population (31 million people) live in these states, which gives a good balance between urban and rural.

The state of London has a population density more than three times that of the next most dense region, justifying it being its own state, as it is likely to have unique requirements even when compared with other metropolitan states. The other 9 metropolitan states have a population density over 1000 people per square kilometer – more than any US state, and higher than Harris County, Texas (Houston) or Los Angeles County, California. Finally, Surrey and Essex bridge the gap between metropolitan states and rural states, being a mixture of urban and rural in the commuter belt of Greater London.

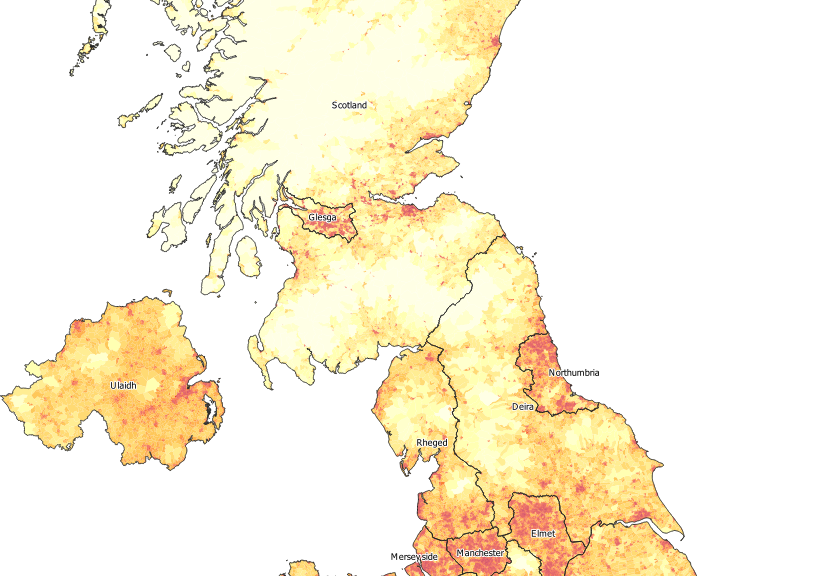

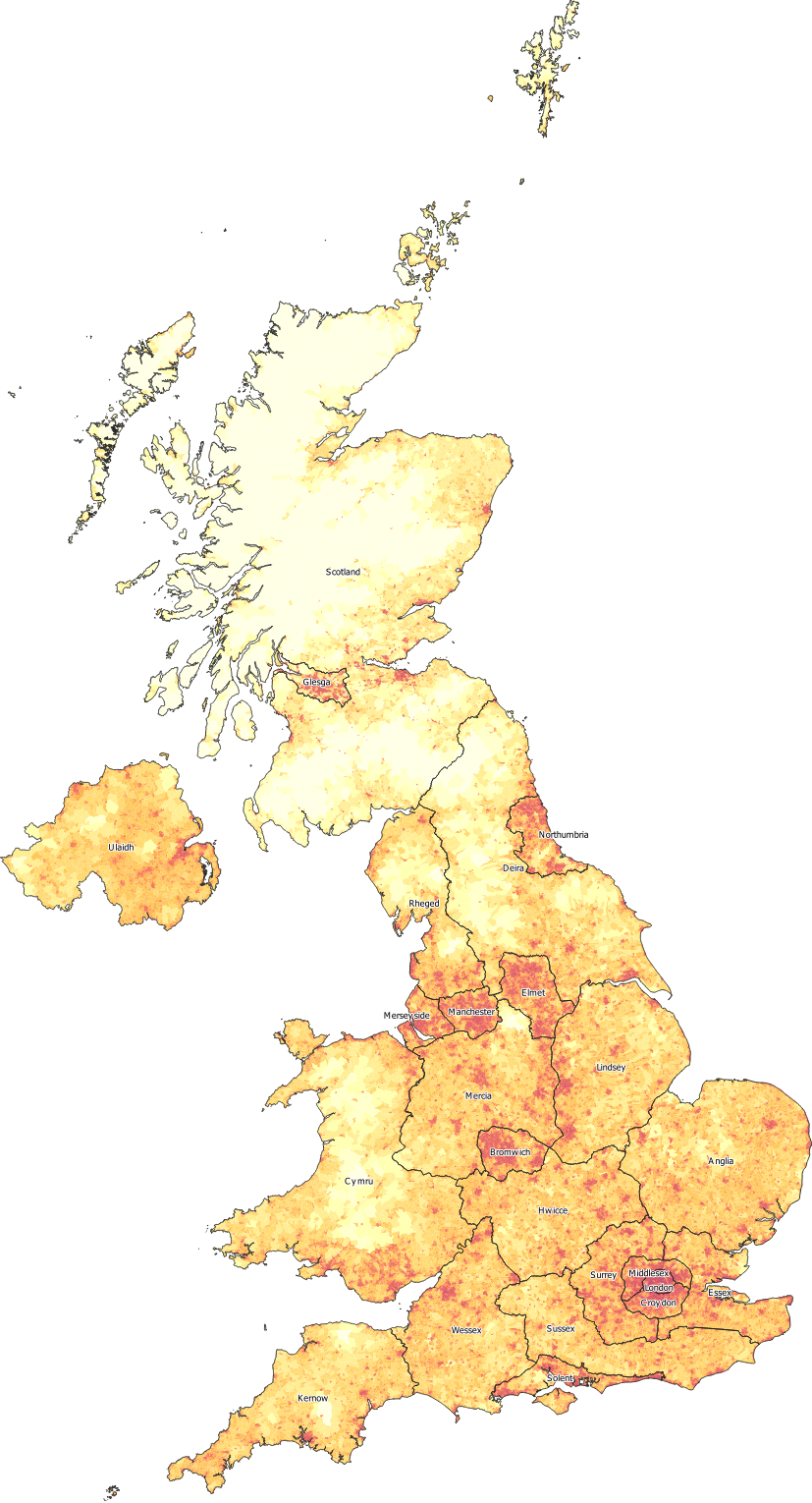

You can see the population densities of the different states if we draw these proposed borders onto a map showing the population density of each census tract. In the map below, the yellow shaded areas have a population density below 10 people per square kilometer, the red shaded areas have over 1000 people per square kilometer, and the various degrees of orange are in between:

Is 24 too many states? After all, the “Regions” proposal only created 12. Personally, I don’t think so – the smallest covers just over 1.6 million people – in between the sizes of the US states of Hawaii and Idaho, and almost 3 times the population of Wyoming. This is clearly a functional size, and this number of states allows them to have their own individual characters, without feeling like they are a random jumble of dissimilar areas. Many federal countries have a comparable number, or even more states than this:

| Russia | 85 Federal Subjects |

| US | 50 States + DC |

| Nigeria | 36 States + Federal Capital Territory |

| Mexico | 31 States + Mexico City |

| India | 28 States + 8 Union Territories |

| Brazil | 26 States + Federal District |

| Argentina | 23 Provinces + Buenos Aires |

| Venezuela | 23 States + Capital District |

| Germany | 16 States |

| Malaysia | 13 States + 3 Federal Territories |

| Ethiopia | 12 States |

| Canada | 10 States + 3 Territories |

| Austria | 9 States |

It is also worth noting that by changing the borders away from the existing county and district borders, I have broken local government. It is generally accepted that local administrative units should be directly subordinate to states, and therefore should not cross state lines. There is therefore some work to do in adjusting the counties and unitary authorities that make up the UK to be compatible with this proposal. Don’t worry – this post is already more than long enough, so all those maps can be saved until the next post.

16 Replies to “A United Federal Britain”

I absolutely adore this! I have been toying with something similar in my head, and it is fun to see your conclusions. I am not British myself, but I did put this idea (https://imgur.com/a/lgmcOWv) together. I think the use of Rheged and Elmet are great, and I defer to your understanding of demography and configurations. I worked on a bunch of the flags (updating them on Illustrator, &c.) and so maybe it can be of use to you! Let me know if you want .svg files

Thanks – I’m glad you found it interesting. I’m pleased to see that you made use of the ancient kingdoms of Hwicce and Lindsey too!

I think there are many hurdles to overcome before any plan for a Federal Britain could come to pass, as any proposal inevitably upsets someone, but I wanted to try to get beyond the usual (and uninspiring) 3 countries, 9 regions model that is so often the default.

Excellent article, thank you. I have a question about an earlier article though, if that’s okay. In “Arguments for a UBI – Conclusion” your final graph makes a powerful conclusion, but there doesn’t seem to be any data available for download to check the calculations. Could you provide that and/or a worked example for how the proposed policy would affect someone earning the UK average wage (apparently £35k p.a.).

Thanks! No problem at all. The final graph is loosely based on income data from this website:

https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/income-tax-liabilities-by-income-range

Unfortunately, this dataset only provides income within a few set ranges, so to generate the graph I needed to apply some assumptions to get a dataset by percentile. The first assumption is that incomes vary smoothly (i.e. there are no sudden step changes), while the second assumption is that the remaining adult population that doesn’t show up in this table (23.2 million people) earn somewhere between £0 and £11,850 (amounts that are low enough to not pay income tax, and therefore not show up in the government’s income tax statistics).

Given these assumptions, it is possible to create a power-law line of best fit that gives very similar results to the government’s dataset. The formula I used for this line is y=x/((P-x)^(4/9)) where P is the total adult population of the UK, x is the total number of people earning below a particular income of the population and y is personal income. As an example, from the dataset, the number of people earning below £20,000 should be 23.2m + 4.1m + 6.2m = 33.5m, and using this formula we get 20,000 = 34.7m/((54.2m-34.7m)^(4/9)). Not perfect, but as a line of best fit goes, sufficient for a graph.

It is important to note that this graph does not account for any income from government benefits that people might receive under the current system – this is too dependent on individual circumstances to be able to include on a graph by percentile (https://atlaspragmatica.com/comments-on-ubi-posts/#graphing-existing-benefits). Many people on the left hand side of the graph would be eligible for benefits, but they are not calculated based on income alone – what people receive ranges from the situation of many homeless people who earn nothing yet receive no benefits, to the situation of the “working poor” renting in London who might earn £20,000 p.a. and be eligible for an additional £10,000 in housing benefit. At the end of the day, the latter group are likely to lose out somewhat under a UBI, but I would argue that subsidising rent in an expensive area is far less of a good use of government funds than helping someone to get off the streets (https://atlaspragmatica.com/comments-on-ubi-posts/#some-benefits-claimants-losing-out).

Regarding your second question – I can provide an example for how the proposed policy would affect someone earning £35k p.a.:

In the 2020/21 tax year, a gross income of £35,000 would result in paying Income Tax of £4,498 and National Insurance of £3,060 leaving a net take-home income of £27,442.

Under the proposed UBI and tax code, this gross income would be taxed at 47%, resulting in Income Tax of £16,450 but the UBI of £8,000 would also be received giving a net take home income of £26,550.

Thank you for that detailed answer. I agree with everything you’ve said.

Given that the hypothetical person would be £892 worse off (2.5% of their gross salary), does that mean that they would be in the red region of your final chart? That’s not implausible, but it suggests that someone earning the (mean?) average full-time wage is in the top 22% of highest earners.

This could be one of those unintuitive examples of averages, like the fact that 99% of people have more than the average number of legs.

Yes – you are correct. The break-even point at which the current tax code and the proposed UBI tax code result in the same take-home income is £31,000 above which people would have slightly higher taxes. The mean full-time wage is significantly higher than what 50% of people earn (the median), largely due to very high earners pushing the mean up (incomes are pareto distributed).

Digging a little deeper though, looking at the Office for National Statistics website, it looks like the £35,000 figure is actually “Mean Household Disposable Income”, which is the income “after taxes and benefits” (the “Median Household Disposable Income” is given as around £30,000). Scaling these figures up to their pre-tax amounts gives £46,000 and £39,000 for mean and median respectively, but this is ignoring the “Household” in the name. It is unclear from the ONS what exactly the average household is, but according to https://www.statista.com/statistics/813380/average-number-of-adults-per-household-uk/ it is 1.9. This gives a mean gross income per adult of £24,200 and a median gross income per adult of £20,500. Of course, while we have factored out the tax, we have not been able to factor out the benefits, so these are both inclusive of benefits in some way, and therefore will still be overstated to some degree.

Taking a median from the income tax liabilities table from my previous comment gets you to £15,000 (half of the adult population of 54.2m is 27.1m. 23.2m people earn less than £11,850 and 4.1m people earn more than this but less than £15,000. This comes to 27.3m, so the median person probably earns around £15,000).

This can be compared with the UK GDP per capita of $42,950 = £32,200. This is a mean, so will be higher than the median earnings, but it is not a measure of individuals incomes – it is measuring the broader domestic economy, so will be skewed upwards by domestic companies paying salaries to non-residents and dividends to international shareholders.

Going back to the idea of households, it can be stated that households with 2 earners would have to be earning a combined gross household income of greater than £61,000 (2 x £31,000) before they saw higher taxes.

All of this is further complicated by the fact that some of the people with low or zero incomes will actually be “stay-at-home” partners of wage-earners, therefore their combined “household income” may in fact still increase on net. Households in this situation are effectively almost guaranteed to see a tax cut due to the measly nature of the “Married Couple’s Tax Allowance” which only allows you to transfer £1,250 of your personal allowance to your spouse. Under the UBI tax proposal, a couple where one person has income and the other has zero income would still receive UBI for both people. A £16,000 UBI coupled with a 47% flat tax rate is actually a tax cut for absolutely everyone (albeit a very tiny one for millionaires… Also most millionaires are good at avoiding taxes, so most will find a clever way for their spouses to utilise their personal allowance, therefore making this no longer apply).

Fantastic analysis, thank you again!

Do you foresee any issues with separating the urban areas from the surrounding rural areas so completely? Could this further accelerate the urban/rural divide? While the populations may be well balanced, could such a divide hinder the balance of wealth and opportunity?

On the one hand, as with any change, it is probably inevitable that further tweaks might be needed to address anything that arises. That being said, I think the urban/rural divide is something that is already far bigger than we tend to appreciate through the course of our everyday lives.

Much like how South Sudan’s independence didn’t itself cause South Sudan to become one of the poorest countries in the world – it was already that poor, but didn’t collect its own statistics separate from the rest of Sudan.

I don’t think the divide itself should be particularly affected by such a separation, but what it would do is make any disparity abundantly obvious to the federal government, allowing funds to be directed to states that needed it the most. The existence of predominantly rural states would also mean that these funds would be far more likely to be used by a rural state for the benefit of its rural residents, rather than being earmarked for city regeneration projects as might be the case in a state with large cities but a large rural minority.

Another important factor is that these are states, and not separate countries, so people still have opportunities to move. Obviously if schooling in rural areas is so sub-par that people can’t compete for jobs in towns and cities, this is a problem, but this is more likely to be resolved by a state government that has a vested interest in investing in rural communities. Actions such as reducing rural bus routes (as they are less profitable), in order to focus on the more profitable urban bus routes (as has happened in Yorkshire in recent years) would be far less likely to happen with a predominantly rural electorate.

I like your plan overall, but personally I would consider ensuring that each state has at least one major urban centre to act as a source of revenue and influence to support the rest of the state more independently of the federal government. So this would probably look more like the 12 states you had at the start of your article, perhaps with London remaining broken down a bit more.

Otherwise you will probably end up with rural states that are highly dependent on federal support and therefore have less autonomy and more limited opportunities. The American analogies you give are good ones, but the problems aren’t only due to disparities in population counts. With purely urban and purely rural states, I believe you’ll eventually end up with an accelerated version of what’s happening at the moment; a brain and youth drain from the rural areas to the urban ones, which will in turn bring back some of the disparities we have currently – where large sections of the younger population end up concentrated in fewer states, diluting their voting power. This could perhaps be rectified by pairing up each urban area with a rural one, and leaving the different administrative approaches that are needed to the local government level.

I agree with you that a completely rural state with no substantial population centres at all would probably struggle economically. I think however, that there is significant wiggle room between carving out a metropolis that is big enough to be a state in its own right, and leaving a rural area with no demographic focal points.

As can be seen in the next post on local government, every state does have at least one “city” district within it. Deira has York and Hull, Kernow has Plymouth and Exeter/Torbay, Ulaidh has Belfast and Sussex has Hastings/Eastbourne (as well as Basingstoke, which I didn’t give its own district as it was slightly too small, but is nevertheless a fairly significant population centre in the region).

This is a fairly good reason for Cornwall itself (exceedingly rural, only 500k population) to not be its own state, but if you were to combine Sussex’s 1.64m people with Solent’s 2.48m to give you a state with a “mixed character” of highly urban with highly rural, it would mean that the people of Brighton, Portsmouth, Southampton, etc. would significantly outnumber the people living in the rural Downs and Weald. This disparity would naturally lead to the state prioritising investment in the cities, and even if a lot were devolved further to local government, it would be easy for the state government to earmark funds for “critical infrastructure” that still predominantly favoured the cities.

From what I can tell, the brain drain you describe is already happening, and has already accelerated in recent years. There are many reasons for this, but a big one has to be the chronic underfunding of rural services and infrastructure. Even if a rural state were dependent of federal funding, that is at least their funding to use. As part of a state containing a metropolis, rural areas can easily be starved of funding without it being obvious, as the state as a whole still has plenty of money. From a “Return on Investment” perspective, it is always going to be easier for a state to justify spending its money in cities, after all, that new road they’re building will benefit so many more people than the other road they could have built in “the middle of nowhere”.

The principle of this is great, but the final map tries too hard to make all of the regions a consistent size and ignores existing physical, political and cultural boundaries. For example, your Essex region is cut in two by the Thames Estuary, and a toll bridge. This could make movement between the two sides really impractical and which side would you put your administrative base in? London is massive and you might want to split it up but that completely ignores the fact that huge number of people on the outskirts commute into the centre, and therefore it makes sense in terms of tax collection, transport, energy ect. for it to be one region. Also, by making areas more consistent in population there is an even greater disparity in area. A massive region like Deira would spend a huge amount more money on roads, railways, policing, schools, ect, which somewhere like Northumbria has a lot less land for new homes and infrastructure. It makes sense for Tyneside to sit within a greater Northumbria region, rather than dividing the city and the country. Finally cities have much greater economic activity, the GDP of London is around a 1/3 of the GDP of the whole country, so the rest of the country will suffer massively if London are able to keep and spend their own tax revenues.

I really like what you’ve done, but Kernow is the Cornish name for Cornwall, if you were to call Devon that too it would piss off both counties (who aren’t the best of friends, take it from a Cornishman 😅). Devon wouldn’t want to be named what is a Cornish name and Cornwall may not want to share it, so may I recommend something based on Dumnonia, the old name of the Celtic kingdom which contained both Counties? It may be a less inflammatory name choice.

Thanks! Yeah – as I mentioned at the start of the post – naming things is an absolute minefield.

If anything like this were actually implemented, I would suggest that the residents of each region have a vote on what they’d like the region to be called. This would hopefully result in a name that at least a majority of residents could get behind (especially if they used approval voting).

I’ve seen similar proposed regions named Dumnonia before, and have no problem with the name – I find that Latin names for places are generally very aesthetically pleasing. I opted for a Cornish name as a deliberate attempt to raise the profile of the language, which whilst only prevalent at the very tip of Cornwall now, was spoken as far East as Bristol (or where Bristol would be built) in the 6th century AD.

I have heard similar complaints about “Ulaidh”, which is the Gaelic name for the North part of the island of Ireland – picking an unpopular name there would probably restart the war, so best just to let the residents decide.

Other issues that people have raised are “Essex” containing Kent, and “Sussex” containing Winchester. I have no idea how problematic these are for people, and don’t have a problem with other names being used, but I do think the current names for the official Regions of England are particularly uninspired.